Click on the photo to see a larger version.

J.

E. Autry was Richard White's great great grandfather.

J.

E. Autry was Richard White's great great grandfather.

J. E. (John English) Autry was my mother's mother's mother's

father.

I chose to qualify for membership in the Sons of Confederate Veterans

on

his Confederate service record.

Within the family, J. E. Autry was apparently called "English" to distinguish him from a number of relatives by the same first name, including his father, an almost 20 year older half-brother by his father's first marriage to Betsie Rory, and another half-brother from his mother's first marriage to James Murphy, John Murphy. John English Autry was the oldest son of John Autry by his second wife (the widow of James Murphy), Barbara ("Bubby") Rebecca McMillan. The birth year shown on his grave stone is an error. He was born, presumably on 29 August, but in 1827, not 1820, in Cumberland County, North Carolina. All census records that have been found consistently show him to have been born in 1827, and besides... in 1820 his father John Autry, Jr., was still living in Cumberland County with his first wife and their children had all grown up and left home. By 1840 his parents were living in Sumter County, Georgia. The Autry family holdings in Sumter County were in the vicinity of Freeman Road, about 4 1/2 miles south of the town of Andersonville and just about the same distance from the place where Camp Sumter Prisoner of War Camp, commonly known as Andersonville Prison, was to be created by the Confederate government in late 1863.

J. E. Autry was the grandson of John Autry, who served with a

brother Alexander Autry, both of them captains in the Wilkes County,

Georgia

Militia, in the American Revolution. For more information about Revolutionary War Captains John and Alexander Autry, click here.

On 5 April 1863, at 43 years of age, J. E. Autry was mustered into Company G, 64th Georgia Volunteer Infantry Regiment at Macon, Georgia. His brothers James and David Autry also served with the 64th Georgia Infantry, the various companies of which were mustered at towns in South Georgia and brought together at Quincy, Florida, in February 1863. The raising of the 64th Georgia and its posting to Florida were part of an initiative by Governor James Milton of Florida in 1862, to draw resources from nearby parts of south Georgia and Alabama, to aid in the defense of Florida. The Confederate government cooperated in that effort by attaching certain specific Georgia counties extending north to Sumter County, Georgia, to the existing Department of Middle Florida of the Confederate Army, making it the Department of Middle Florida and South Georgia, and by suspending the Conscription Act as it would have applied to units raised in that area, thus apparently making volunteers in new units raised in the area eligible for an enlistment bounty.

After brief stays at Camp Cobb near Quincy and at Camp Leon beside the railroad just a few miles south of Tallahassee, by April the 64th Georgia Infantry was bivouacked further south on the same railroad, at Camp Randolph, which the 64th Georgia Infantry built at Wakulla (sometimes known erroneously as "Wakulla Station"), in Wakulla County, Florida. The 64th Georgia Infantry spent until August 1863 at Camp Randolph training and serving as an element in the defense of the coastal area of North Florida and the railroad from St. Marks to Tallahassee. Then it moved to Savannah, Georgia.

The 64th Georgia came back to Florida and participated in the Battle of Olustee (also known as the Battle of Ocean Pond) on 20 February 1864. At Olustee, the 64th Georgia Volunteer Infantry Regiment was a component of Brigadier General Joseph Finegan's Army of East Florida, and of Colonel George P. Harrison's 2d Brigade of that Army along with the First Florida Infantry Battalion, 32d Georgia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 1st Georgia Regular Infantry Regiment, and 28th Georgia Artillery Battalion. Though far from the main centers of the conflict and one of the smallest major battles of the Civil War, Olustee was also one of the bloodiest for the number of troops involved. The 64th Georgia was the first unit engaged at Olustee, and it remained engaged throughout the battle. At Olustee the 64th Georgia Infantry lost 107 of its approximately 800 men (17 dead, 88 wounded, and 2 missing... approximately 13% casualties). At the height of the battle, which occurred in a virgin pine forest on open and level terrain and was conducted without benefit of prepared positions, several Confederate units stood their places in the line without ammunition for a time.

The Sixty-fourth Georgia experienced its first combat at Olustee. Sent out from the Olustee defenses early in the afternoon to skirmish with the advancing Federals, the regiment played a prominent role throughout the battle. Its official casualties were listed at seventeen dead, eighty-eight wounded, and two missing. Included among the casualties was its commander, Colonel John W. Evans, and Major Walter Weems, who were wounded, and Lieutenant Colonel James Barrow, who was killed. After the death or wounding of the unit's field officers, Captain Charles S. Jenkins "conducted the regiment throughout the most fearful periods of the fight." (Confederate Roll of Honor: Southern Casualties at the Battle of Olustee, p. 48)J. E. Autry appears to have incurred a minor wound in the battle at Olustee. He was hospitalized in the General Hospital in Guyton, Georgia on 24 February 1864. (Guyton is a small town slightly to the northwest of Savannah.) No reason for this hospitalization was recorded, but the date and record of subsequent hospitalizations imply a puncture wound to the left leg. The Battle of Olustee was fought at close range in a thick virgin pine forest and swamp. I waded through that swamp myself for several hours in February of 1997, so I know how cold and miserable that can be! Both Union and Confederate artillery were deployed at close range at Olustee. The Union artillery was deployed so close to Confederate positions that most of the artillerymen and horses were killed by Confederate musket fire. Because of the unusually close deployment and insufficient depression of the barrels of the pieces, artillery fire by both sides was said to be ineffective in this battle and almost all casualties to have been caused by rifle/musket fire. Although it is just a theory on my part, with no specific information available, I suspect that John English Autry may have been hit by a pine splinter thrown by the high artillery fire at Olustee. Although he is not listed as a casualty at Olustee in the recently published Confederate Roll of Honor: Southern Casualties at the Battle of Olustee, the hospitalization at Guyton was on the same day as many Confederates who were known to be wounded at Olustee were admitted there and the Roll of Honor is considered by its authors to be potentially incomplete... although its totals are a greater number than the totals given shortly after the battle. I have applied to the compilers of the Roll of Honor to add J. E. Autry's name to future editions.

After the Battle of Olustee the 64th Georgia returned to Savannah

for

awhile, then in early May of 1864 the regiment joined the Army of

Northern

Virginia in its final campaign, the defense of Petersburg. In

Virginia, the 64th Georgia Infantry Regiment was incorporated into Lt.

Gen. A.P. Hill's Corps, Maj. Gen. William Mahone's Division, Girardey's

Brigade. The

64th

Georgia had major involvement in the defense of Battery 16 during

Grant's

attempt to flank the Army of Northern Virginia by landing Beast Butler

and troops under his command at Bermuda 100 on the James River, and in

the Battle of the Crater after the Union Army's engineers exploded a

huge

mine under a salient on the Confederate defenses on 30 July 1864.

The 64th Georgia was one of the Confederate units closest to the

Crater. As far as can be gleaned from records, J. E. Autry would

have been involved in these battles.

J. E. Autry was admitted to Wayside and Receiving Hospital or General Hospital No. 9, Richmond, Virginia, on 30 September 1864 and was sent on to 1st Division Jackson Hospital in Richmond, Virginia on 1 October 1864. Admission records show that the diagnosis was "Ulcer, L. Leg", most likely an unhealed wound that had festered under the conditions of trench warfare in the Confederate lines at Petersburg. He remained in Jackson Hospital until 17 February 1865 (4 1/2 months) at which time he was furloughed for 60 days. The Army of Northern Virginia surrendered before his furlough was over. There is no record that J. E. Autry surrendered anywhere. Apparently he somehow avoided parole and taking of an oath of loyalty to the government of the United States...

J.

E. Autry had married Mary McQuien on 11 June 1854. Records

in Sumter County, Georgia,

spell the family name McQuien and McQuean, and oral history from my

grandmother Mary Haire indicated that Mary's father himself spelled the

name

McQuien. The McQuien spelling variant is still used to this day

in Scotland, mostly in the vicinity of Glasgow. They moved

near

Whigham in Decatur County (now Grady County), Georgia in 1869... the

same

year that their daughter who became my great grandmother, Forest

Preselle Autry,

was born. Family legends refer to tax bills and land grabbing

Carpetbaggers

as the reason for the move. I presume that they lived in or near

Sumter County during the War... but so far I have found no marriage

record and they were also apparently missed by the census-taker in

1860. Thus, to date I have found no way to be certain where they

resided from 1854 to 1869.

J.

E. Autry had married Mary McQuien on 11 June 1854. Records

in Sumter County, Georgia,

spell the family name McQuien and McQuean, and oral history from my

grandmother Mary Haire indicated that Mary's father himself spelled the

name

McQuien. The McQuien spelling variant is still used to this day

in Scotland, mostly in the vicinity of Glasgow. They moved

near

Whigham in Decatur County (now Grady County), Georgia in 1869... the

same

year that their daughter who became my great grandmother, Forest

Preselle Autry,

was born. Family legends refer to tax bills and land grabbing

Carpetbaggers

as the reason for the move. I presume that they lived in or near

Sumter County during the War... but so far I have found no marriage

record and they were also apparently missed by the census-taker in

1860. Thus, to date I have found no way to be certain where they

resided from 1854 to 1869.

On 7 February 1877 John English Autry died of consumption

(tuberculosis)

that he contracted while serving in the Confederate Army. He was

buried with several other Confederate veterans, all in unmarked graves,

at Antioch Church in Decatur County, Georgia. Years later his

widow

(Mary McQuien) went with her granddaughter... my grandmother Mary Haire... to place a stone on

his

grave. Unable to identify the specific grave, they returned to

the

farm and unloaded the grave stone from the wagon to the barn. It

was still there when I was a child. Later the barn tumbled down

and

was demolished. The last time I saw it... some 25 years ago...

the

grave stone was lying on its back in the grass behind a cousin's home,

near the site of the old barn... chipped around the edges

from being hit by a lawn mower blade. The inscription includes

the

phrase, "Gone but not forgotten."

I believe that is true,

and will do my part to see that it remains so, no matter where the

grave

stone lies.

Mary McQuien Autry never remarried. She raised four children as a widow, and reputedly was known among local merchants as a very hard-bargainer. My mother said that some would close their stores when they saw her coming... From 1893 to 1905 she collected a Confederate widow's pension from the State of Georgia in Decatur County. Under an act of the 1905 Georgia legislature, effective 1 January 1906, Grady County was created from the eastern part of Decatur County and the western part of Thomas County. The Autry place was in this new county, near its western boundary. Mary McQuien Autry collected the pension in Grady County in 1906 and 1907, but over the years her once firm signature quavered then turned to an "X" as she lost the ability to sign her name. I believe that she suffered, as did my mother and grandmother, from Alzheimer's disease. After 1907 apparently her health declined to the point that she no longer collected the pension. She died in 1920, some 43 years after her husband, and is buried in Butler Cemetery, about half-way between Whigham and Calvary in Grady County, Georgia, beneath a grave stone that matches in style, the one that was never placed over her husband's grave.

Going by directions from my grandmother, then in Ft. Myers, Florida,

relayed by my mother, then in Tampa, I looked for Antioch Church

several

times over the years without success. I found it just over

the county line in Climax, to the northwest of Calvary in current day

Decatur

County, on 11 October 1997. There are no signs of burials having

occurred prior to about 1910 in the small graveyard to the northwest of

the church. I spoke to the preacher's wife and found that

the

congregation dates to 1857. There is oral history that the church

site was a few hundred yards to the north at one time... in a location

now occupied by tree farming. The date of the move and whether it

included constructing a new building or moving the existing structure

are

unknown; however, the church building appears to me to easily have been

built prior to 1877. The preacher's wife indicated that as a

little

girl she was told not to play near the southwest corner of the area now

enclosed by the cemetery fence because of unmarked burials in that

vicinity.

With that, I take it that at long last I have probably come as close as

I ever will, to finding John English Autry's final resting place.

A final photograph (below) shows part of the Autry family in front

of their home south of Whigham, Georgia, at a date estimated to be

around 1910. J. E. Autry's house was on the south side of what

was in my youth essentially a two-rut driveway ending at the

house. Those two ruts gave way to asphalt pavement some years

ago, and the paved road has been named Haire Lane. The one-armed

man seen in the photo with one foot on his buggy-step,

was John English and Mary McQuien Autry's son, Ira Autry. Their

daughter, my great grandmother Forrest Preselle Autry, is to be seen

standing at the

top of the front steps; and it is thought that is her brother Eli Autry

sitting to her left on the porch rail, and and her brother John

Alexander

Autry standing to her right. Sitting in the rocking chair is my

2-great

grandmother Mary McQuien Autry, widow of John English Autry. This

photo came from Nathaniel Autry and was e-mailed to me by a descendant

of John English Autry's brother David, Neil Paschal Johnson.

Notes

About Some of the Photographs:

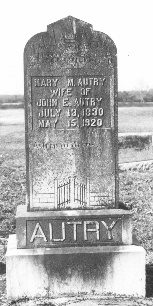

1. The photo of the grave stone

was made in the back yard of my first cousin once removed, Mrs. Rosa

Le Osteen Clayton, in 1976, while I was working to fulfill a

requirement for a class at Florida State University, in historical

architecture. At the time that the photo was taken, the old corn crib

that it had rested in for many years had been demolished and the grave

stone lay on the ground probably around a dozen to 50 feet north of

where the old building had once stood.

2. The photograph that I

have identified as being that of John English Autry is from a tintype

that

I found on that same day in 1976, in the "Old Haire place"... the

farmhouse on that same property

which was then unoccupied and in a considerable state of disrepair...

including loss of its roof to wind damage in two areas. I

photographed a copy of that tintype, and have tried to positively

identify it ever since... but so far that has not been possible.

In the absence of positive identification, I can only say that based on

his appearance, family resemblances, and the ante-bellum

clothing

style, I believe that this is a photograph of John English Autry taken

perhaps not long after he married Mary McQueen in 1854 (tintype" [more

properly known as ferrotype since the photographic plate was made

of iron and there was no tin in it] photography was first

patented

as "Neff's Melainotype" in the United States on 19 Feb 1856; however

the process seems to have been around as early as 1853 in both France

& the U.S. and perhaps commercial use of the process preceded

the patent?). I

reproduced the photo as it appeared in the tintype above... but all

tintypes are "first impressions", each unique, and like a negative...

though tintypes were printed directly to a positive image... the

photographic depictions that tintypes present are all REVERSED (left to

right). In the large copy

that is linked to the small one, I un-reversed the photo so that its

subject can be seen

in proper perspective for the first time in some 150 years. At

any rate, the family resemblance seems unmistakable to me. In

fact, here is a small version of the un-reversed photo beside one taken

of me in 1965... with his daughter, my great grandmother Forrest

Preselle Autry, pictured to his left:

A Further Note about the Tintype:

I spoke to someone with a lot of knowledge about early photographs

today... she deals in them. Her opinion is that it is unlikely

that this tintype is ante-bellum; but that the subject matter confirms

that the photograph that it embodies within it is ante-bellum.

She

said that the speckles on the tintype are highly uncharacteristic of

tintypes but that they are very characteristic of an earlier and more

fragile photographic medium known as the ambrotype. This was

another inexpensive photographic method that actually pushes the

earliest date of the photo back to 1851 or slightly thereafter.

Upon reflection, I agree with her. Let's put it this way... I

have very extensive experience in reproducing "black and white"

photography, and one of the very first things that I noticed about this

photo is that its "blemishes" had no surface manifestation at all...

but rather appeared to be an integral part of the photograph.

This argues quite well for this tintype being a photographic copy of an

earlier ambrotype that had begun to deteriorate. She said that

such copies were not uncommon at all, and that they were done for

various reasons including just being able to distribute copies to

friends and relatives, and... apparently... to preserve the images

previously captured in fragile and deteriorating ambrotypes. I am

very comfortable with this assessment, and in fact it agrees with my

belief that this photo should date to about 1853-1854 when John English

Autry would have been courting Mary McQuien.

RELATED LINKS:

A Note on Sources for this Page

Battle of

Olustee Index Page

Battle of Olustee Battle History

64th Georgia Volunteer Infantry Unit History

Company G, 64th Georgia Unit Roster

Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Private Joseph Thomas Stansell Gleaton

Return to: